Bodenständigkeit: The Environmental Epistemology of Modernism

Kenny Cupers

The Journal of Architecture, 21:8, 2016

Focusing on late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century imperial Germany, this article examines how environmental thinking shaped the development of modern architecture and urban planning. The environment took on an acute importance in the rapidly industrializing and colonizing Empire, prompting a wide range of projects, from landscape conservation and the design of garden suburbs to pioneering soil research and colonial planning. What made these diverging scientific, political and design undertakings understandable as environmental projects is the notion of Bodenständigkeit—the quality of something rooted in, or uniquely appropriate to, the soil on which it stands. This idea was more than just the symptom of a romantic or anti-modern mind set; it was part and parcel of a novel environmental way of thinking, prompting discussions about the future and conservation of urban and natural landscapes, the form of new buildings and settlements, and the methods of domestic and overseas colonization. Bodenständigkeit, this article argues, is not only a primary category of early environmental conservation but the first version of an environmental determinism that would come to structure twentieth-century modernism at large.

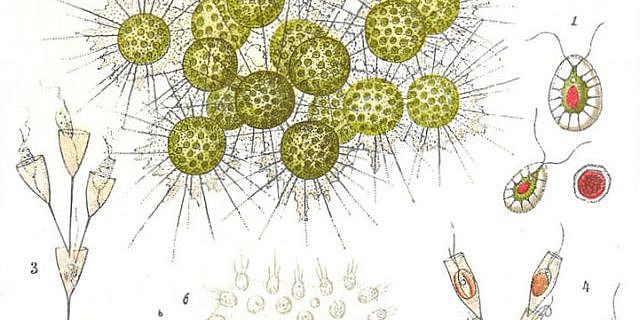

Image: From: R.H. Francé, Streifzüge im Wassertropfen, 1907 © Kosmos

Quick Links